Above my piano I have a couple of pictures depicting two singing children, a cat, a dog and a bird. They’re posters from an opera called Brundibar, written by the composer Hans Krasa – a cousin of my great grandmother’s. Brundibar the opera is so significant – culturally, historically and musically – that there is a festival named after it,The Brundibar Arts Festival. The opera is performed regularly throughout the world – it is being performed this month by Opera North Youth Company in Leeds and Gateshead. It has been turned into a picture book by Maurice Sendak. Sometimes I look up at these colourful posters on my wall with my relative’s name on them, and feel inspired. Other times I turn away; they make my stomach churn and my nose prickle. They make my heart sink. These posters represent to me everything that music is, and can be. But they also remind me of the very darkest times in my family’s, and the world’s, history.

Brundibar was written as an entry for a Czechoslovakian children’s opera competition by Hans Krasa in 1938. Before the winner could be announced however, Jewish music was banned by the Nazis. But music can find its way even past evil, and within a year secret rehearsals of Brundibar were underway at a Jewish orphanage in Prague. Before he could see it premiere however, Hans Krasa had been arrested and deported to Theresienstadt concentration camp, shortly followed by nearly all the orphanage staff and children.

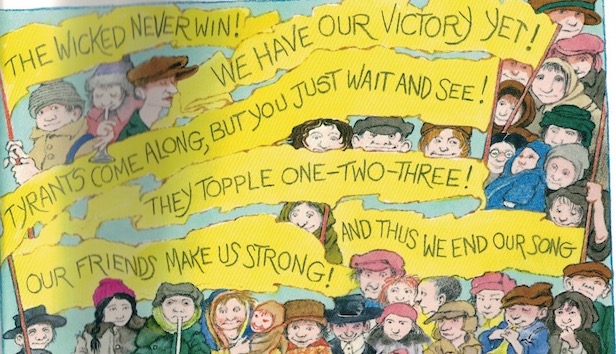

In Theresienstadt living conditions were squalid and the death rate was high. But the Nazis, masters of deception, presented the camp to the outside world as a “model ghetto” in an attempt to dispel growing reports of the exterminations and atrocities actually being carried out in their camps. As part of the disguise, musical endeavours were permitted. So with a partial copy of the piano score smuggled into Theresienstadt by the Prague orphanage director (“as precious treasure” he later said), Krasa was able to re-orchestrate and rehearse his opera. He had a half broken piano, a few string and brass instruments, and children who sang. When it had finally been rewritten and rehearsed, Brundibar was fully exploited by the Nazis for their propaganda purposes (apparently missing the irony of the opera’s plot – children resisting and finally overcoming a bullying tyrant). Within just one year, It was performed officially 54 times for SS officers and visiting dignitaries, and dozens of times unofficially in dormitories, hallways and yards for other prisoners. Keen to deceive a visiting contingent from the International Red Cross in 1944 who were inspecting conditions at Theresienstadt, the Nazis arranged for an extra special staging of Brundibar. After all, what could be lovelier and more wholesome than a group of musicians and children singing? The Red Cross committee were successfully fooled by the elaborate hoax and, convinced that conditions were good and the prisoners well treated, left the camp. That 55th performance was the last one. Within two weeks, the Nazis had sent Hans Krasa and most of the musicians and the child performers and chorus to their deaths.

I cannot imagine the horror of being in that camp. I cannot imagine the horror of being a child there. My hope is that the music and singing brought some form of comfort to many of the incarcerated children and adults. It perhaps gave them a means of expression. It allowed them to be part of something creative in the face of dreadful adversity. It allowed them, for just a few minutes, to forget where they were.

The power music has on us is strong. After all it is used as a form of therapy for people traumatised by war. I like to think that the prisoners in the camp may have felt something like hope when they sang. A small light in their continuing darkness. So on Holocaust Memorial Day this week I will light my candle and look up at my Brundibar posters, and remember Hans Krasa and the rest of my murdered ancestors – the Krasa and Heimler families. And I’ll remember the musicians in Theresienstadt who kept playing. And the children who, through the most horrific and brutal of circumstances, continued to sing.